ASNR Member Spotlight: Dr. Thomas P. Naidich, ASNR 50-Year-Member

Dr. Thomas P. Naidich, MD, FACR, FASPNR, joined the ASNR in 1974 and has remained an active member ever since. In this month’s Member Spotlight, we are not only celebrating Dr. Naidich’s 50 years of ASNR membership, but also his enormous contributions to the field of Neuroradiology as whole.

Please enjoy this Q&A with Dr. Naidich unabridged and in his own words:

How did you become interested in Neuroradiology?

We are a family of Radiologists, including:

- My cousin David Naidich, a prominent Chest Radiologist at NYU

- My brother James Naidich, a prominent Interventional Radiologist at Northwell in Long Island, NY

- Myself, Thomas Naidich, at Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai, NY

- My niece, Michelle Naidich, Neuroradiologist at Northwestern University in Chicago

When I was in Medical School, and my brother was a Radiology resident, he and his wife would have me over for dinner, followed by a fascinating review of current Radiology Cases. Pavlov succeeded. I chose Radiology.

In 1972 I had to choose a Fellowship. I chose Neuroradiology because it seemed the most difficult of all the specialties of that time. I felt that I knew pretty well how to do most of the other studies then done (most now obsolete) and thought it best to invest one additional year in Neuroradiology. I really wanted to be excellent in performing and interpreting plain X-Rays of the Skull and Spine, Pneumo-encephalography, Pantopaque myelography, Direct stick Carotid and Vertebral Angiography, etc.

In 1972, no one I knew had heard of EMI scanning. I decided on Neuroradiology late and was accepted into the Neuroradiology Fellowship at NYU by Dr. Irving Kricheff and Dr. Norman Chase, to begin July 1973. By good fortune, the NYU program was to receive the EMI Mark 1 Scanner February 1974.

In 1972, the NIH was fostering the new specialty of Neuroradiology. NYU already had a full complement of 4 Fellows, but they called the NIH and got a 5th budget line, so they could hire me. I was, literally, the 5th Fellow.

At that time NYU had four rotations for the Fellows, each repeated 3 times during the year. Over the 12 months, they were:

- 1 month (X 3) – Plain X-ray Diagnosis: Head & Neck, Skull, Spine

- 1 month (X 3) – Pneumoencephalography

- 1 month (X 3) – Pantopaque Myelography

- 1 month (X 3) – Mixed Catheter and Direct Stick carotid and vertebral angiography.

What to do with the 5th Fellow? A 5th Fellow did not fit those rotations easily.

Solution: Send him to the morgue for 3 months. The Manhattan Medical Examiner’s Office was on the corner of 1st Avenue and 30th Street, immediately next to NYU and Bellevue.

So, for the first 3 months of my Fellowship, I went to the morgue. Each morning, I bought the worst newspapers, found out who shot who, who jumped, who died in an accident, and then went in to see my (deceased) patients. I was very well treated. I got to take out 10-20 fresh brains a day. Since death by drug overdose was a crime that had to be evaluated by the ME, I saw large numbers of young brains, as well as the aged. I could examine the skulls and brains in detail, finding fractures, subdurals, intraparenchymal hematomas, strokes, aneurysms, dissections, colloid cysts and a wide variety of other neuropathology. I could absorb their nature, in color and texture, and see their effects on the rest of the brain: herniations, hydrocephalus etc. That exposure set the direction of my career as an anatomic neuroradiologist/neuropathologist.

I also had the opportunity to study in detail the course of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA). I injected the lumen with micropulverized barium for later radiography, systematically categorized AICAs course and variations, and compared it to the posterior fossa angiograms that were just being described by the French school and by Drs. Huang and Wolf at Mt. Sinai. That review was awarded the Cornelius Dyke Award of the ASNR (1975).

I’ve never looked back. Many of the great advances in Radiology, like CT and MR, have been applied first to Neuroradiology, because the living brain doesn’t move too much. The imaging techniques could be worked out first in Neuroradiology, and then applied to the chest and abdomen after motion compensation was perfected.

Why did you join ASNR and remain a member for 50 years?

I joined the ASNR because my professors were all the founders of the ASNR: Norman Chase, Irvin Kricheff, Norman Leeds, etc. We all met approximately monthly at the New York Neuro Club, to present unusual and instructive cases. Dr. Juan Taveras from Columbia, and Dr. Gordon Potts from Cornell were active participants. Their enthusiasm for Neuroradiology was infectious. They welcomed us — the very junior trainees — to share it with them. Their delight in being the first to shout out the “Great Diagnosis” on unknown cases, made us competitive, but competitive in the best way: for seeing more closely, for knowing more, and for assisting in the care of the patients. Once I got carried away. No one was calling out the diagnosis, so — without thinking — I called out a diagnosis no one else had mentioned. At first, they bristled a little, then quieted, thought, and asked the presenter, “Was he right?” I was. And they congratulated me, instead of being angry. Pavlov strikes again.

I joined the ASNR to become a part of these great doctors and teachers, who welcomed me in as a (junior) colleague. These were people with whom I could share a passion. We could learn together and do our work better because of what we learned. These physicians soon became acquaintances, then colleagues and later, best of all, friends.

I remained a member of ASNR, because it was the place to learn, to join with colleagues to work out ideas, and to have a place where showing the results of your hard work earned respect and friendship. The ASNR provided the social reward of friendship, the academic rewards of publications and presentations to advance your career, and sparks of new ideas that led to new investigations. At one ASNR cocktail party, I was chatting with a friend, Dr. Robert Quencer of Miami, when we both realized there was need to evaluate and categorize the application of sonography to Neuroradiology. That work led to my being asked to be the Opening Speaker at the first-ever Educational Seminar for the ASNR. The topic chosen was Neurosonography! (ASNR New Orleans: Feb. 1985). That also led to the well-received text Neurosonography (Springer). Only in a Society of like-minded academics, could such a series of events transpire.

Further, no one can explore all avenues of research by himself/herself. Just as my conversation led us in one direction, hundreds of similar conversations among others led to their research, their discoveries, and their presentations back to us at the next annual meeting of friends and colleagues. The ASNR provides the venue for learning and teaching, and the joy of knowing more at the end of the meeting than you knew before.

Can you tell us more about your teaching methods?

I believe that learning to read images in the absence of exposure to the real tissue in the OR and the mortuary is like learning to interpret ink blots correctly. You can read the pattern, but don’t understand all that goes into the creation of that pattern, vs. another pattern.

As analogy: To be a buyer of sheets for Macy’s, you need to know thread count. To be an excellent neuroradiologist you need to have mastered your subject by spending time in the OR and in the mortuary.

I have made myself a fixture at the weekly brain cuttings in pathology (200 -300 brains a year). I prepare and bring to brain cutting printouts of key images from the premortem CT-MR-Angiograms of the brains to be cut. We review them first to determine the best way to cut the brain and to identify any additional sites of smaller injuries to be detected and studied histologically.

I bring the Radiology Residents, rotating medical students and as many Neuroradiology Fellows as can be spared to join in the brain cutting, to hold the brains in their hands, so they can integrate real anatomy, brain weight, extent of atrophy, sizes of ventricles etc. into their interpretations. Often, in the next room, they are doing a fresh autopsy, so the trainees get to see, in fresh tissue, the skull, dura, arachnoid, origins and exits of the cranial nerves, courses of normal and atherosclerotic arteries, veins and dural sinuses, and any hemorrhages, infarcts or tumors. In post-operative cases, the trainees get to see what the post-operative skull, dura, craniotomy defect, surgical cavity and any residual hemorrhage or tumor look like. In this way, the trainees learn the expected appearance of normal and of pathological material and can integrate that into their interpretations of imaging studies. Real Tissue, Not Ink Blots.

In teaching the Residents and Fellows, I stress that the goal we should hold out for ourselves and for our trainees should be “Useful Interpretation of Neuroimaging.” Description of the lesion is basic and needful, but to be useful,

- you should know how the information you provide influences patient management, and, further,

- what information is useful for each case, so you can provide it pro-actively.

I stress that to be useful, you should have knowledge of what surgical corridors a neurosurgeon would consider for treating the lesion you have just found. Your reports should then include a description of what potential complications would lie along one corridor vs. a different surgical corridor.

- As a very simple example: In a patient with a herniated disc at C5-C6 disc being evaluated for potential anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF), you should point out that the images show unilateral vocal cord dysfunction, mandating that the surgery not be performed via anterior approach on the opposite side, lest the patient suffer permanent bilateral laryngeal dysfunction and require a tracheostomy for life. Better still, choose a posterior approach instead.

- To be slightly more thoughtful, in a patient with C5-C6 disc for ACDF, have you commented on whether the vertebral artery ascends anterior to those vertebrae and does not enter the foramen transversarium until C5 or even C4. That anatomic variation could lead to vertebral artery injury on one side, which could be avoided simply by doing the ACDF from the opposite side, or by electing posterior surgery instead.

- Similarly, for an interhemispheric approach to the corpus callosum, “Is the falx hypoplastic or fenestrated?”, and “Do the medial gyri interdigitate across the midline, increasing the risk of vascular or tissue injury due to choice of one vs. a different interhemispheric corridor?”

- Is there a median (triple) anterior cerebral artery (incidence 2-13%) or a bi-hemispheric anterior cerebral artery (incidence 10-20%) that would increase the risk of arterial injury and stroke if the surgical corridor chosen to reach a lesion is an interhemispheric approach.

- If you find a parasagittal meningioma at the mid one-third of the superior sagittal sinus, you already describe the patency of the sinus (or not), but do you comment on whether adjacent convexity-draining veins enter the superior sagittal sinus anterior to, or posterior to, the site of sinus occlusion?, and whether those veins course along the surface of the meningioma en route to the sinus? If unanticipated, both situations could increase surgical risk.

All the above is an attempt to illustrate why bringing the trainees into the mortuary adds significantly to their growth as Neuroradiologists. In one sense it is even better than going to the OR, since they get to see the whole brain, not a limited surgical exposure, and since they actually get to handle the tissue.

I believe that we should include rotations through Gross Neuropathology as part of the Neuroradiology Core Curriculum (always allowing exceptions for religious concerns or personal discomfort).

I hope these few examples may help to make my point. I believe that teaching from the brain makes us and our trainees better Physicians and Neuroradiologists.

In summary, I joined the ASNR to improve my knowledge and to become a better Neuroradiologist. I have remained because of the excellence of the teaching at the meeting, and because the ASNR provides a wonderful opportunity to work with, learn from, and befriend others who share my passion for Neuroradiology. Together we are better.

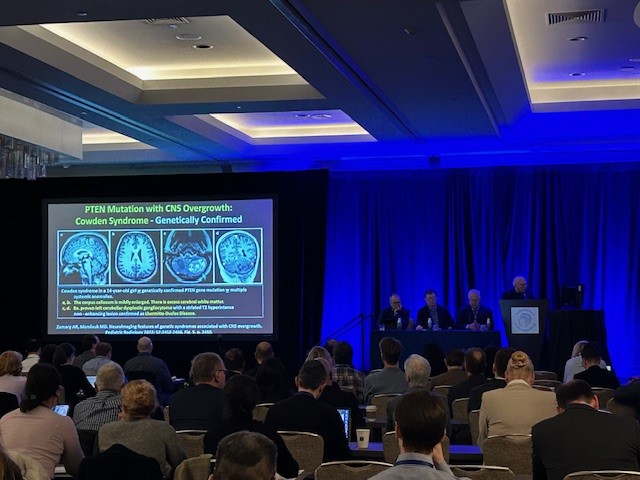

Dr. Naidich on stage lecturing during the 6th Annual Scientific Meeting of the ASPNR (2024). (Photo courtesy of Dr. Amy Juliano)

Dr. Naidich at Mt. Sinai (photo courtesy of Dr. Amish Doshi)

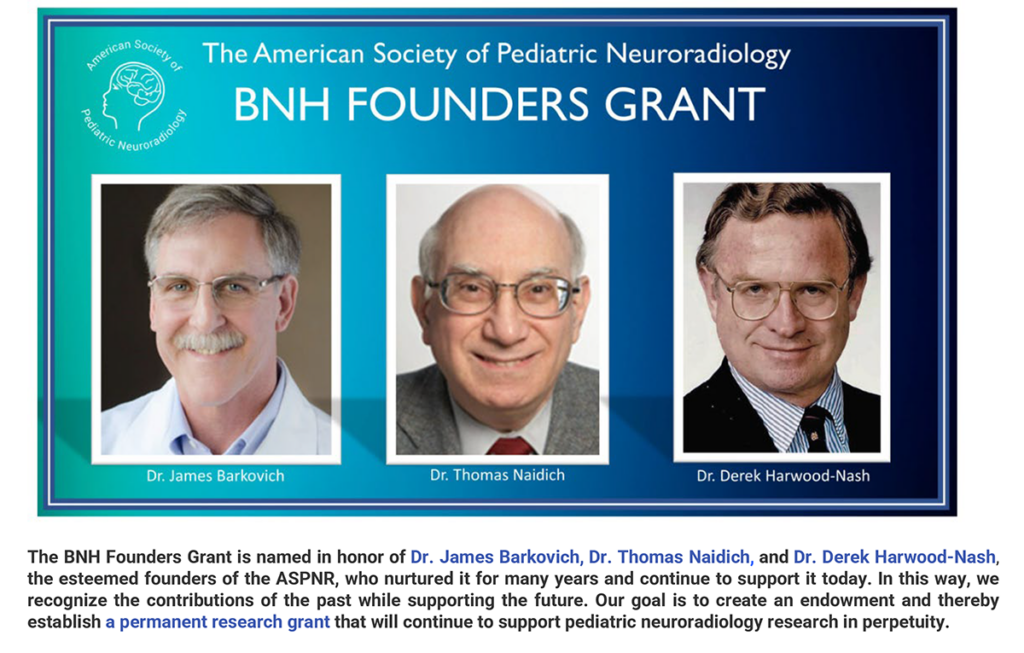

BNH Founders Grant announcement (photo courtesy of Dr. Thomas Naidich)